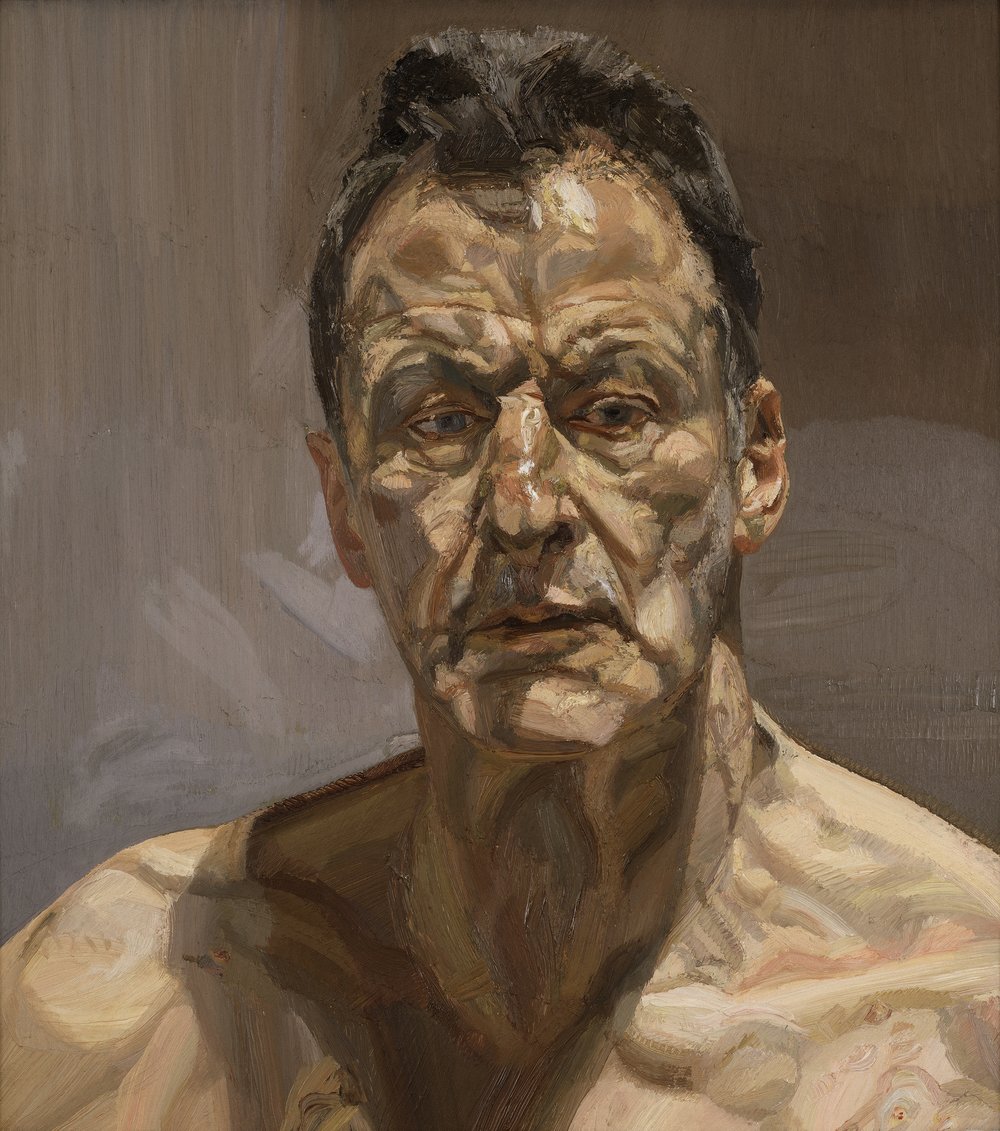

REFLECTION (SELF-PORTRAIT)

BY LUCIAN FREUD

In anticipation of what is set to be a monumental exhibition of Lucian Freud’s self-portraits at the Royal Academy this autumn – an exhibition we are making a film about – I’d like to focus on one of his most famous of works: a 1985 rendering that captures the modernity and complexity of this 20th-century master of portraiture.

Born in Berlin in 1922, grandson of the renowned father of psycho-analysis Sigmund Freud, Lucian Freud emigrated to Britain in the early 30s and was naturalised in 1939. After the war (he was a seaman) he studied art at St Martin’s in London and quickly established a reputation for both his work and, it is fair to say, his behaviour. All of these factors – and more – play into what became the main focus if his art – portraiture and self-portraiture: an unblinking, somewhat impassive, honest analysis of sitter and self.

The Royal Academy exhibition focuses on the self-portrait – in total he did 50 self-portraits. What is notable about this direction in Freud’s work is that this was a specifically 20th-century brand of realism. Unlike earlier artists famous for their self-portraits – Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Gauguin – Freud had to contend with a world in which an accurate depiction of the self could be easily captured instantaneously with the click of a camera. Freud’s portraits had to offer something the modern camera could not. They had to uncover a different kind of truth.

I’ll be honest: I am still learning about Freud (our film is directed not by me but my colleague David Bickerstaff) and am learning how to look at and appreciate his work. So why have I chosen this example? I start having been influenced of course by what I have read about Freud. This 1985 portrait does seem to back that up. The thick brush strokes and the pink and turquoise hues of the artist’s shoulders make it unashamedly clear that this is a painting and not an attempt at photographic accuracy. The body is deliberately more fluid and elastic than the rigid lines and heavy shadowing of the face. Such placement sucks us into the stern face of the artist. His arched brows, set jaw and richly coloured irises fix us in place, deliberately confusing as to who is scrutinising and who is being scrutinised. It may be a self-portrait but the stare is still confrontational to us the viewer.

Freud consciously assigns this transfixing quality to his own face. Further depicting himself upright, implicitly nude and relatively devoid of emotion, this rendering is an expression of strong masculinity. The self-portrait is revealing – not in the same way as a photograph, but as a man’s perceived vision of himself.

Set against Freud’s dozens of other self-portraits, Reflection becomes a part of a gripping narrative of self-presentation, ageing and the investigation into one’s own identity. Even alone however, Reflection reveals an intriguing dialogue between Freud the sitter and Freud the artist.

I hope you will share with me an enthusiasm to find out more about this leading British artist of the 20th-century.

* * *