THE FIGHTING TEMERAIRE

BY J. M. W. TURNER

Back in 2005, the BBC’s Radio 4 Today show organised a poll to discover ‘Britain’s favourite painting’. Or, let’s be fair, those Britons who listen to the Today show and could be bothered to vote. 118,000 people did indeed do so and the results were thus:

1st: The Fighting Temeraire – Joseph Mallord Turner with 31892 votes (which was 27.00% of the accepted votes)

2nd: The Hay Wain – Constable with 21711 votes (18.38%)

3rd: A Bar at the Follies Bergere – Manet with 13218 votes (11.19%)

4th: The Arnolfini Portrait – Jan van Eyck with 11298 votes ( 9.57%)

5th: Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy – Hockney with 8890 votes (7.53%)

6th: Sunflowers – Van Gogh with 8603 votes (7.28%)

7th: Rev Walker Skating – Raeburn with 8189 votes (6.93%)

8th place: The Last of England – Madox Brown with 5283 votes (4.47%)

9th place: The Baptism of Christ – Piero della Francesca with 5028 votes (4.26%)

10th place: Rake’s Progress – Hogarth with 3999 votes (3.39%)

Personally, I see some red flags there: where is Millais’ Ophelia? That painting once topped a similar poll. Nothing by Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo and yet a Piero della Francesca in the top 10? Is he that popular? And forgive my ignorance perhaps but I have never heard of The Last of England by Ford Madox Brown. Nevertheless it is fascinating that Turner’s painting is in this (albeit flawed) poll: the number one choice. So let’s see if we can understand why.

Personally I love Turner’s works and this is no exception. We’ve yet to make a Turner Exhibition on Screen film, but the possibility has been floating around for a while, and I am still exceptionally proud of our episode of Great Artists based on his artwork. Turner’s narratives tap into my interest of English/British history. His scale and ambition are so frequently breath-taking. His technique is impressive and multi-layered, his use of colour peerless, his exploration of light powerful and moving.

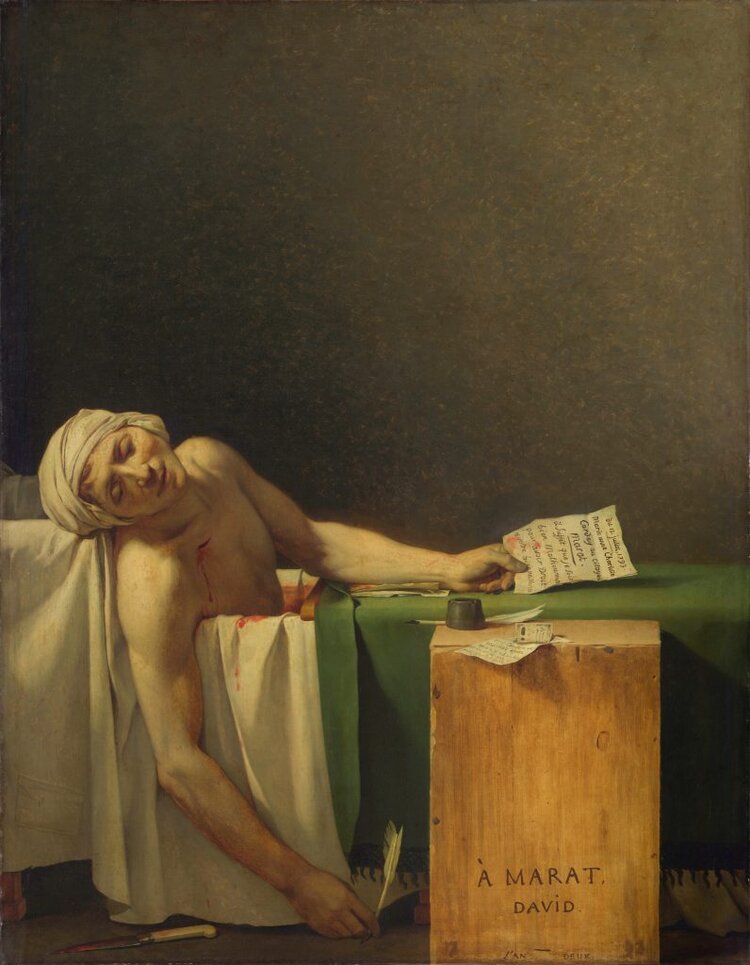

I’ve worked on two films about Nelson and the Battle of Trafalgar in our Great Commanders collection. I simply could not read enough about life in those “wooden worlds” – those fighting ships. I was brought up knowing about key battles in our history like Trafalgar and the more I researched it, the more incredible it became. The Temeraire was a key ship that day and now here it is being towed down the Thames to be taken to bits. It is the end of an era – the industrial revolution is well & truly under way. This is the steam age: the age of wind has passed. So there is plenty to peer at, plenty to place you in the late 1830s when history seemed to move so fast.

So the narrative is clear (which helps) and taps into our sense of ‘when Britain ruled the waves’. But the storytelling alone is not enough to explain why it is so popular. Look carefully at how Turner controls your eye. He makes sure you look first on the left at The Temeraire and then through brilliant use of diagonal lines and spots and streaks of white your eye follows a clear path across the painting until finally you are left looking at the fine detail of the building in the hazy distance. Do you see the Houses of Parliament and the clock tower (‘Big Ben’)? Turner was hugely influential on the impressionist painters that saw his work but what is interesting here is this mix of detail. Look again at The Temeraire itself – grand, ethereal, carefully rendered – and the sea and sky which is a sublime ‘impressionistic’ mix of colours and brushstrokes. This all makes it a beautiful and powerful painting that offers all sorts of visceral pleasures. Like a good film, it is a gripping story allied with high craft.

Whisper it quietly, but this surely can be called a masterpiece. Is it ‘the nation’s favourite’? Who knows. But is it one of the greats of British art? Yes. Turner loved it enough to never sell it so he rated it highly. There are dozens and dozens of contenders for favourite paintings awaiting a lunchtime pop-in to the London’s National Gallery (for those fortunate enough to stop by once their doors reopen shortly) but I suspect this piece will make a fair few visitor’s top 10 list.

* * *